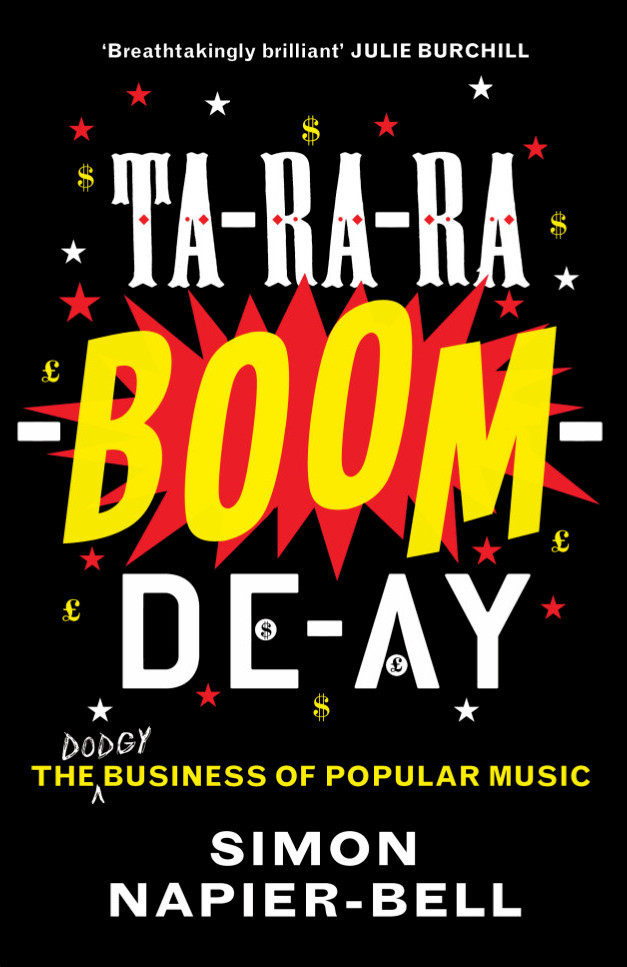

Having managed iconic acts from The

Yardbirds to Marc Bolan to Wham! as

well as claiming a number of production

and writing credits, including co-authorship of

Dusty Springfield's You Don't Have To Say

You Love Me, Simon Napier-Bell has been at

the sharp end of the music industry during some

of its most successful decades. But, having now

published his fourth book, Ta-Ra-Ra-Boom-De-

Ay, which comprehensively charts the evolution

of popular music over the last 300 years, Napier-

Bell has an academic perspective on the business

that few others can match.

Forget reminiscing about a pre-iTunes era,

Ta-Ra-Ra-Boom-De-Ay traces the music industry all

the way back to the British Parliament's establishment

of the right of ownership for creative work in 1713.

From there, Napier-Bell gives a detailed and blunt

account of music's journey from the promotion and

sale of sheet music for amateur pianists, right through

to today's difficult transition to the access model of

music streaming - highlighting and critiquing the

biggest stars in musical history on both the artistic

and executive side along the way.

We won't spoil the ending, but what's clear in

Napier-Bell's take on things is a love of the biz in

all of its filthy glory and some real optimism for

the future at a time when headlines everywhere else

seem to be willing the mighty industry to finally

admit defeat. Don't hold your breath, says

Napier-Bell.

"The thing that comes up time after time is

that this industry is in decline, but I haven't seen

any decline or even a crisis in the music industry,"

he tells Music Week. "The overall figures of money

being spent in the music industry in the last three

years have gone up every year. What's in decline is

the sale of records - what's increasing the overall

pot is the income to publishing companies and

most of the publishing is owned by the record

companies, what they lose somewhere they make

somewhere else.

"The whole point is that we have a $68 billion

a year pot and as long as the public is willing to

spend $68 billion a year, there are going to be

entrepreneurs who come along and find a way

of taking it from them. It may no longer be for

records, it may be for streaming or something that

we have no concept of yet, but it won't go away."

What have you taken from all this research into the

music industry and its history?

Once I started my research for the book, I changed

my mind about quite a few things. One was

that there's actually no way that artists are taken

advantage of; artists are part of the business, they

come in to it to make money. [Over the years]

the artists have come in and adapted what they're

best at doing, making music, for the technology of

the music business. In the beginning, the business

was based on sheet music, so the artist wrote sheet

music. Sheet music had to be sold to amateur

pianists, so publishers were very keen on simple

songs that only had a few chords with a small range.

They found this wonderful formula of eight bars

repeated and so on. Then, when records came, songs

became three minutes long. Before that, a hit song

was at least 10 minutes, you went on stage, sang it

and got the audience to join in... three minutes was

ridiculously short, but with the technology of records

three minutes became acceptable and so on until the

writer in the present day.

The idea that the industry somehow screwed the

artists' wonderful art just isn't true. The artists were

willing cooperators and entered into the business,

albeit from another angle. So I felt much more

sympathetic towards the business [after researching

for Ta-Ra-Ra-Boom-De-Ay].

The other thing that came up really clearly is

that everyone who moved the business forward

from the beginning right up until recently, all of the

figures who were respected and revered on both the

music and industry side, did so because they were

hedonistic, greedy and self-interested. I couldn't

find anyone who we respect who sat down in an

almost charitable sense and said, "I want to improve

the industry." One or two people were like that but

they were so boring we can't remember them.

Duke Ellington was asked at The Cotton Club,

which only had white audiences, to write jungle

music because that's how they saw black people. So

Ellington invented in his mind what he thought

they meant by jungle music, which became Duke

Ellington's music. That was Duke Ellington

entering into the commerciality of music and, if

you like, going along with their racism. Then, if

you come forwards to the Erteguns - wonderful in

business - but [Atlantic Records founder] Ahmet

was so respected and was basically a guy who loved

a good time, loved black music, loved drink and

drugs and didn't like getting up in the morning. He

was a very fun-loving, much loved person but there was no,

"I've got to improve the music industry and make it a

place to be proud of." All of the recent

people as well, had this self-interested attitude

which created their success. So the music industry

is one unlike any other, because it hasn't been

created by dedicated people specifically educated for

that industry, it's been totally dominated by free-

wheeling, fun-loving, slightly greedy, sometimes

corrupt people who love music.

So, when executives say it's all about the artist and

letting their creativity flow, do you think that's

probably a bit disingenuous?

Look what vinyl was. It was gift from heaven - a

quarter of a penny's worth of vinyl could be pressed

and turned into a record that could be sold for five

shillings. Nowadays, one penny's worth of vinyl can

be pressed and sold for £10. It's a 10,000% profit

margin and nobody wants to give up on it. That's

why they all have huge buildings and limousines.

Who would want to lose that?

The music publishers have always had to deal

with a tiny bit of money coming in from lots of

places and slowly making a big amount of money.

The record companies just got a big bit of money

right from the beginning.

Of course you need a label, but do record

companies care about the artists? Ask an American

record boss how many artists they pay private health

insurance for. Not one. How many employees?

Every single one. They treat artists as an ingredient

of a hit record.

That's not how it started. I do agree that in

the '50s and '60s the people who started record

companies in England and America, like Tony

Stratton-Smith or the Erteguns, loved music and

artists. Some might have been a bit sharp with

their practices or careless with money, but they did

love music.

But records were this gift from heaven and as

the corporations were taken over by the people

who cared most about the money and least about

the music - with the 80s being the big switch time

when the accountants came in - everyone thought

in units and the artist just became this thing that

had to be dealt with. I can't believe that's all turned

around all of a sudden. What happens when an

artist makes a record [the executives don't like]

and asks for it to be put out because it's their art?

It doesn't go out, they're told to go away and

make one that will sell. And so they should be!

I'm not objecting - the artist should be part of the

business. I'm not objecting to the attitude where

the artist is seen as an ingredient - artists should

see themselves as an ingredient. But for a record

company to pretend that they only care about the

artist is a bit disingenuous.

Has your view on all of this changed compared to

when you were a manager?

Well, I'm not anti-record company, as a manager

I loved the record companies but you loved them

like an enemy - it was a game! You went to war on

behalf of the artist but without an enemy you didn'l

have a war to fight. It was a permanent battle to

get what you needed and wanted and the end result

was benefit for both sides. I always enjoyed it and

I had loads of friends at record companies. Both

sides knew it was a battle that had to be fought and

compromised on. Writing the book hasn't changed

any of that, but I do look at the artist as much less

put upon.

We have musicians complaining about getting

a bad deal in the new age, but musicians have

always gotten a bad deal. Artists have always come

to a compromise with the music business to make

themselves into stars and, frankly, in the future

they'll always get both ripped off and looked after

to some degree. If they aren't looked after then

there won't be any new stars and the record industry

relies on star musicians - but the regular, back-up

musicians have never really benefitted.

I don't think anything will change much. There

will be entrepreneurs who make the money and

artists who are prepared to compromise to make the

most money they can.

How do you think the consumer perceives the

music industry today?

Much more cynically than it deserves to be seen,

probably. To see it cynically you'd have to think

it was highly organised to cheat, corrupt and lie

but actually it's not like that, it's rather a mess. It's

not a huge corrupt machine and I don't think the

business is nearly as cynical as the public thinks it is.

Do you think artists are getting long enough now

to establish a career? It's something that a lot of

people ask these days, but is it necessarily just a

modern problem?

It's always been cut-throat but situations affect

things. If you go back to before the 20s, when

there was no radio and a hit song usually took a

year and a half to establish, the stars then were

the songwriters not the people who sang the song

because there was a whole variety of people who

sang the song.

Then radio came along and people said, "That's

the end of the music business, music is free, no-one

will ever buy anything again." Suddenly with radio

the cycle of making a hit came down to about three

months. Hits came and went much quicker and

sold only a fourth or a fifth [of what they used to].

The overall money in the industry was the same but

each song was earning less, which in a way is what

we're talking about with artists now. More artists

get access now because of the internet but far fewer

of them really get to that big stage of being a major

worldwide name. The ones that are signed up to

record companies are getting less time to develop,

that's for sure, but they're not usually signed up

until they've gone through some development stage

in what they do on the internet. I don't think many

people are going to get signed absolutely cold,

which in the past they might have been, so it's just

that the chance to develop has to happen before

they sign to the record company rather than after.

I don't think it's any more or less cut-throat than

before, it's just that the timings are different.

Recording artists were totally huge in the 70s,

80s and 90s because [of the nature of records]. If

you had an artist coming out with a big new album,

you'd do a huge multi-million pound campaign

and you had to be sure that records were ready

to be sold when that promotion started, so you

had to press a million or two million in advance

and you really couldn't afford to get it wrong too

often. So artists were really pushed by the record

companies to become broader and broader in their

appeal. Cynical critics said they were pushed to the

lowest common denominator, but I don't really

think that's true - they were pushed to refine and

refine until they found a way to express artistry

with the broadest possible appeal. Huge artists

like Michael Jackson, Madonna, Crosby Stills &

Nash and probably acts as recently as Oasis went

through that. That's going to go away because

record companies don't really care about doing that

anymore. A record company now is quite happy to

sell a million downloads whether it's through 50

artists or just one, whereas in the past it really had

to be through one.

Shep Gordon told us a few weeks ago that the

record label's role these days was as a marketer...

In the 60s the managers found the artists,

developed their public image, worked with them on

their music and the record companies didn't have

anybody. In the 50s the chart was the top 10 most

popular songs judged on the sale of sheet music. In

those days a top song was recorded by five different

artists because the important thing was to sell

sheet music. When that chart changed to records,

the record companies didn't have any marketing

because the marketing had always just been the song,

there was no notion of building the

artist. So as that switched, it was the managers that

took over and conceived and developed marketing.

Well into the 70s, it was mainly the managers that

were doing this and some of them became record

executives. Then record companies began to get

very good A&R people.

So what we're seeing now is that it's sort of

going back to what it was in the 60s - the record

companies want someone outside the company

to do all that development and then bring them

something like the finished package. Instead of

being all depressed about it, you should look at it

as much better. Artistic development was always

better in independent hands, rather than corporate,

so it's actually a big step forwards. The thing is

[independents] do need the marketing corporations

For five or ten years now everybody has been saying

that record companies are finished, but if you look

at the Top 20 charts on both sides of the Atlantic,

it's all major record companies. They're not dying.

Do you think the track has become a promotion

tool for other revenue streams?

Well that would be going back to the beginning

wouldn't it? Way back before radio, and even up

until the rock era, as long as the chart was made

up of the Top 10 songs based on the sale of sheet

music, the music was more important than the

artist. Streaming is going to make the actual music

more important than the artist at least for a while

for lots of reasons, a simple one being that you don't

hold a cover in your hand and look at the artist or

read the sleeve notes while you listen to it.

Do you think that owning rights today has become

more important again with the slide away of

physical product? It seems everyone is keen to

retain their rights more than ever.

I think everybody always wants to retain their right:

it's just that if you need money to finance your

career and you don't have any, you take what is

offered to you. From the beginning of publishing,

a songwriter would be offered as little as possible

to get as much as possible - buying the song

for a month's rent or something. That's always

gone on: in the 70s and 80s, admittedly, it got

to new heights, unproven artists and songwriters getting

unbelievable amounts to give away their rights.

I don't think anyone is sure where the industry is

heading, but for sure the $68 billion that's swirling

around isn't going to go down - where it's going

to go and for what, I don't know. Over the last few

years the money has mainly come from live, but

you can't really say it's healthy when most of that

has come from acts that have been around for 20

years. And records aren't healthy when nobody's

buying them, but the industry as a whole continues

to thrive.

Ta-Ra-Ra-Boom-De-Ay, published by Unbound Books, available from Amazon